Week 17 of the 2013 season featured a full spectrum of the NFL’s greybeard totem pole.

At 37, Peyton Manning just capped off the most supreme passing season in NFL history. Quarterbacks are a protected class in the NFL.

They fire bullets over a wall of blockers and are given Witness Protection by the NFL rulebook which protects them from bloodthirsty defenders.

Linebackers are the instruments of destruction tasked with charging through gaps, detonating all over tight ends and colliding with ball carriers at full speed. Each kamakazi hit takes a toll on the human body that cumulate over the years.

MIKE linebackers don’t benefit from rules that protect offensive players, but they are also tasked with being defensive quarterbacks.

Seven rounds after Manning was knighted franchise savior by the Indianapolis Colts, Division III Linebacker of the Year London Fletcher was invited to St. Louis Rams minicamp as an undrafted rookie free agent. Despite being college teammates with Bill Polian’s son Chris, Indianapolis and 29 other teams passed on Fletcher.

He suffered from the same debilitating biological condition that caused scouts to downgrade Drew Brees. St. Louis Rams Director of Player Personnel Charlie Armey would later inform Fletcher that they decided to take their chance signing him as an undrafted free agent because at his 5-10 height, they were sure every other franchise would as well. It was a condition that would cause him to be overlooked in a macro-scope for the remainder of his career.

Fletcher origins begin on the most perilous unit in all of sports— special teams and he would never miss a single game in his entire career.

In Week 1 of the ’99 season, Fletcher started his first full season as the MIKE linebacker against the Baltimore Ravens.

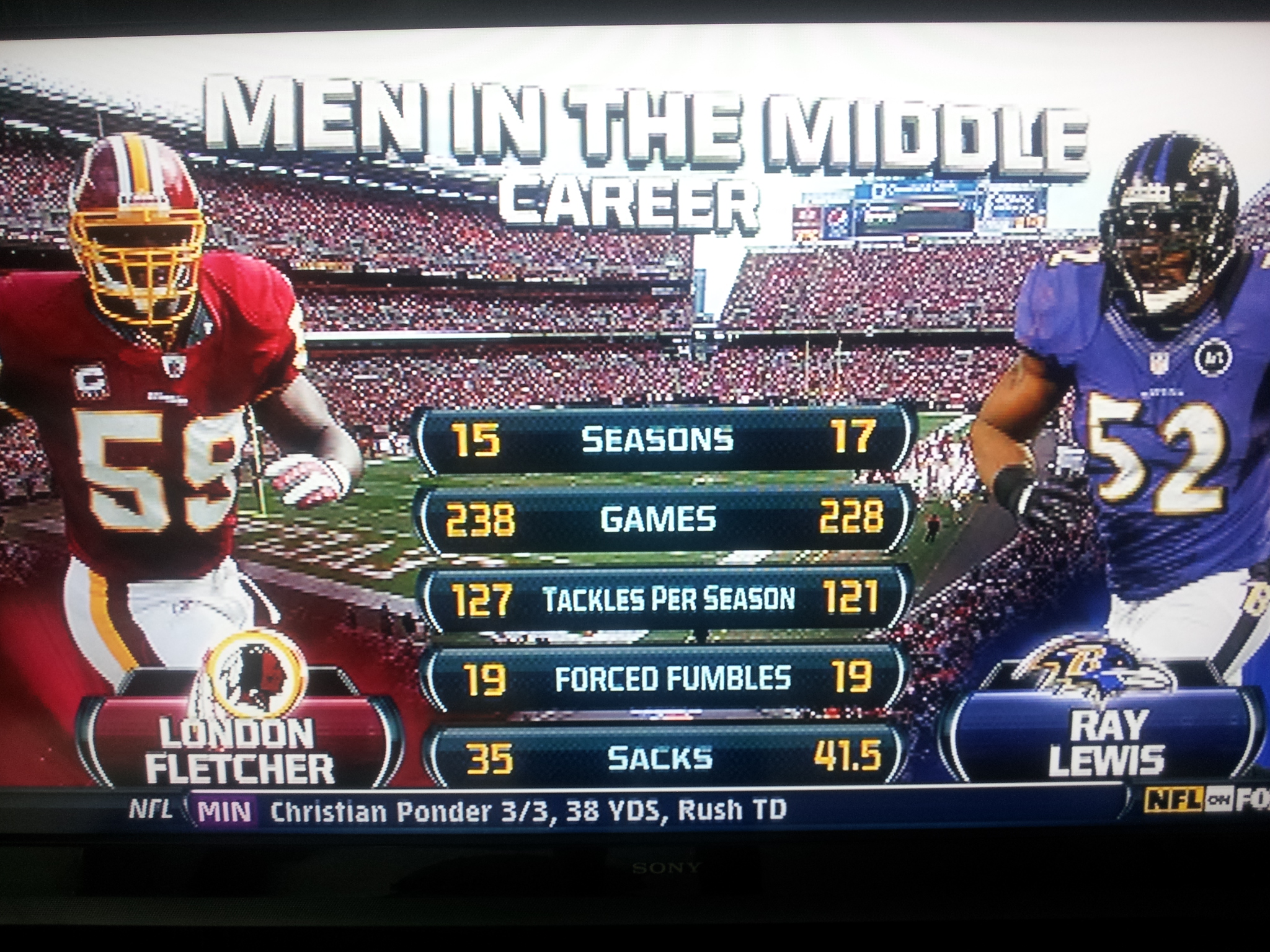

Fletcher quietly wrapped up three tackles in his second start, but was overshadowed by Ray Lewis’ 14 tackles as well as Kurt Warner, Torry Holt and Marshall Faulk’s Rams debuts.

Earlier this season, he broke Derrick Brooks’ record of 208 consecutive starts at linebacker. He would have broken it a year ago, if the Rams hadn’t started out a Week 10 matchup in 2000 against Carolina on the sideline in nickel coverage with five defensive backs.

Hours before Lewis was at the scene of an altercation that would leave two men dead, tarnish his reputation and nearly stripped him of his freedom, Fletcher became a Super bowl champ. In what would become a recurring theme, the Rams’ Greatest Show on Turf offense and Lewis’ trial would be the talk of the league during the offseason while the undersized linebacker who went from undrafted to Super Bowl champ and “All-Madden” team member in two years went unnoticed.

In the first round of the 2000 Draft, the Chicago Bears would select Brian Urlacher and for the first dozen years of the new millennium, they’d become the standard-bearers of the league’s new generation of middle linebackers.

Lewis rebounded from his felony murder case, became the most revered linebacker in NFL history and over a decade later would unexpectedly wound up sharing NFL on FOX chryons that made the unheralded, undrafted, unknown linebacker making his second start at linebacker compare favorably to him.

Lewis was just another cog in a Miami’s first round pro factory monopoly. Fletcher is still the only player from unheralded John Carroll University to have played in the N.F.L. in more than 50 seasons.

That was the apex of acclaim for Fletcher’s career. Fletcher played for one more team in his career than Urlacher and Lewis combined.

Lovie Smith let Fletcher walk in 2002 because he didn’t fit the Cover 2 scheme. However, Coach Gregg “Bounty Gate”Robinson thought he was the perfect athlete to replace Sam Cowart, also a Class of ’98 draftee who was once regarded as one of the elite linebackers in the game until injuries chopped him down.

After Robinson was fired in Buffalo and hired as Washington’s defensive coordinator, he got Joe Gibbs to co-sign fetching Fletcher for five-years and $25 million in 2007.

A few years later, Albert Haynesworth followed Robinson to D.C. from Tennessee and received $100 million.

“Ultimately, here was a guy who did not love to play the game of football. And he came in here and he took Mr. Snyder’s money,” Fletcher told the NFL Network’s Rich Eisen. “Robbed him without a mask.”

Fletcher was a Pro Bowl alternate eleven times despite recording more tackles than any player in the first decade of the new millennium and didn’t play his first Pro Bowl until 2010 after Jonathan Vilma pulled out because the Saints were playing in the Super Bowl.

Any other year Fletcher would have been stayed home, but this was the year Roger Goodell experimented with playing the Pro Bowl in Miami the week before The Big Game.

Urlacher was forced into retirement by a new general manager who wasn’t influenced by the past. Lewis’ retirement announcement before the postseason provided the Baltimore Ravens with a mighty gust to propel them to another Lombardi Trophy.

Fletcher hasn’t experienced a euphoria equivalent to Lewis’ Super Bowl run or matched Urlacher’s crestfallen denouement. Instead, it was a steady resignation that this was the end and the final games became a celebration of his career.

“All in all it wasn’t the year we had hoped for, finishing the year 3-13, very disappointing,” Fletcher told the media after the game. “Everybody had high expectations coming in. We just didn’t get the job done collectively as a team. … But all in all I’ve enjoyed my time here in Washington, playing for the Redskins and representing this organization, wanting to leave a legacy, being able to do that. I think I’ve done that. I played 16 years and accomplished what I was able to accomplish. I feel good about that.”

It was Fletcher’s time to go. Fletcher’s football IQ and awareness have halted his athletic decline, but his inability to keep up with tight ends in his later years has made him a liability in pass coverage.

According to Pro Football Focus, Fletcher's 21 missed tackles in 2012 were also the most by any inside linebacker in the NFL. Keith Brooking and Takeo Spikes, both drafted before him in ’98 went unsigned during the offseason and are still free agents making Fletcher the only linebacker from the ’98 Draft on an active roster.

After their harrowing Divisional Round win over Denver last January, Ray Lewis was informed Peyton Manning was waiting outside the locker room to pay respect to an adversary.

Fletcher ended his career against Peyton’s brother Eli, who will inherit Fletcher’s consecutive games played streak for active players, but there was no Manning waiting for him after the game. Fletcher’s streak of consecutive games played streak will likely end at 256 games unless that one percent overrules the other 99 percent certainty that he would retire. That streak is fourth all-time behind defensive end Jim Marshall, Brett Favre and punter Jeff Feagles.

However, in an interview with MMQB, Tony Gonzalez, whose path from musclebound D-I hoops star to future Hall of Famer mirrors Fletcher, disclosed that he regards Fletcher as his closest rival.

“I’ve loved playing against London Fletcher. What a warrior. We just played Washington, and I caught a touchdown against him—and he was holding me all the way down the field, [Laughs.]” Gonzalez guffawed to Peter King. “I knew he was retiring. After the game, he told me, ‘This is it for me. Enough.’ I knew what he meant.”

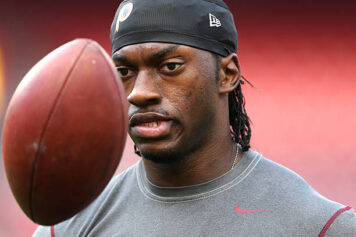

Fletcher is so respected as a team captain and defensive leader that the Redskins placed Robert Griffin III’s locker beside his last summer. However, Sean Taylor is the player Fletcher would have benefitted the most from playing alongside.

“After I was here for a while, during training camp, I told people, 'Why'd you need me? You already got a great leader, and it's Sean Taylor,''' Fletcher said days after Taylor’s death.

Fletcher envisioned the pair being the Ed Reed/Ray Lewis duo on the other end of The Beltway.

"I thought he could have been the best safety in the history of pro football,'' Fletcher said. “He was 6-3, fierce, a hard-hitter, a great cover guy, great speed for a guy his size, great ball skills, incredibly instinctive and had a great passion for the game. Teams didn't challenge him deep.”

Fletcher’s personal legacy as a gridiron warrior is an uplifting story of a stout linebacker from a rough section of Cleveland who crept underneath the radar, but left footprints the size of craters in his wake and permanently caved in the chests of skill position players.

There is a slight downside to Fletcher’s ironman that can’t be ignored. Fletcher is one of the final generations of athletes to play crash dummy with their brains. Balance issues arose after he hid a concussion suffered in the last preseason and subsisted for weeks while he visited specialists who couldn’t diagnose his lost equilibrium. Doctors eventually whittled the cause down to nerve damage in his neck that was a result of the same hit. Fletcher dodged a bullet. Meanwhile, he readily admits that the number of times he's had his "bell rung" is in the double digits.

His continued willingness to play through unreported concussions set a poor example in the opinion of a minority of observers. Fletcher was neglected for much of his career by the national media, but the only question remaining is whether they paid enough attention to recognize that he deserves their Pro Football Hall of Fame votes someday.