In their July 9, 1990 article Kicking Off To Chaos, Sports Illustrated forecast that 30 years from then (our present day), the NCAA would be made up of four major super conferences, with 16 schools in each league. The feature projected 1998 as a target, with the lede:

It is New Year’s Day 1998. You’re comfortably settled into your favorite beanbag chair (they’re back in vogue). Time to take in a little football. You click on the tube and get the Cotton Bowl on PBS, featuring SSWC (Streamlined Southwest Conference) champ SMU against Penn, the Ivy League titlist. Yeech! So you switch over to ABC, where the Sugar Bowl is about to kick off with Miami, champion of the Southeastern Conference, going up against Notre Dame, the country’s sole remaining independent, for the right to face Rose Bowl winner San Diego State in next week’s national championship game.

Today there are several realigned major athletic conferences, among them the SEC, the Big 12, the Big Ten, the Pac-12 and the ACC. They are known as The Power Five. With an eye towards football supremacy and television revenue, these leagues have shuffled their memberships drastically since 2012.

In what ways have these changes impacted recruiting, finances, smaller revenue sports, media coverage, and fan support? Where are the “wins”, and where are the “losses”? How have some moves proved beneficial for some, while detrimental to others? The answers lie in the conferences’ motives toward realignment.

ESPN’s Bomani Jones told The Shadow League, ACC expansion was predicated on the premise Miami and Florida State would be great in football. Miami has never played in the conference championship game. FSU had down years before Jameis Winston. There was similar strategy in bringing Nebraska and Penn State into the Big 10.

Penn State moved into the Big Ten in 1993, to align itself with football powers Ohio State and Michigan, and help balance a top-heavy football conference. Major college football players are not only revenue drivers, they are costly. Ten years ago, when Penn State was giving $2,250 per student to those in it Honors College (whose requisites were a 1400 SAT score and 4.0 GPA), it paid $25,000 in aid to each college football player. Today it pays $50,000 for each football player, to only $4,500 for Honors College students.

When the University of Texas was coached by Mack Brown, the school paid $261,728 per football player, only $20,903 on each student.

To house and feed its players, and pay exorbitant salaries to its top coaches, college football earns money from TV deals, ticket sales, luxury seats. The Big Ten Network made $6.4 million last fiscal year.

“Big Ten Network numbers are up all over the place and are still rising, since Maryland and Rutgers joined,” said Big Ten commissioner Jim Delany at the 2016 Shirley Povich Symposium at the University of Maryland. The BTN reaches 60 million homes, and is available in another 30 million.

Bowl games are another huge cash cow. There are 128 college football programs, and 41 bowl games, which means 62.5% of universities make it to a bowl game. Power Five conference schools earn about $50 million, whether they send a team to the football playoffs or not. Schools selected for the semifinals earn $6 million and others earn $4 million for participating in one of the Big 6 bowls – the Citrus, Alamo, Outback, Ticket City Cactus, Texas, and Holiday Bowls. The mid-majors from the American, CUSA, MAC, MWC and Sun Belt are paid $18 million total per conference. Notre Dame earns $3.75 million.

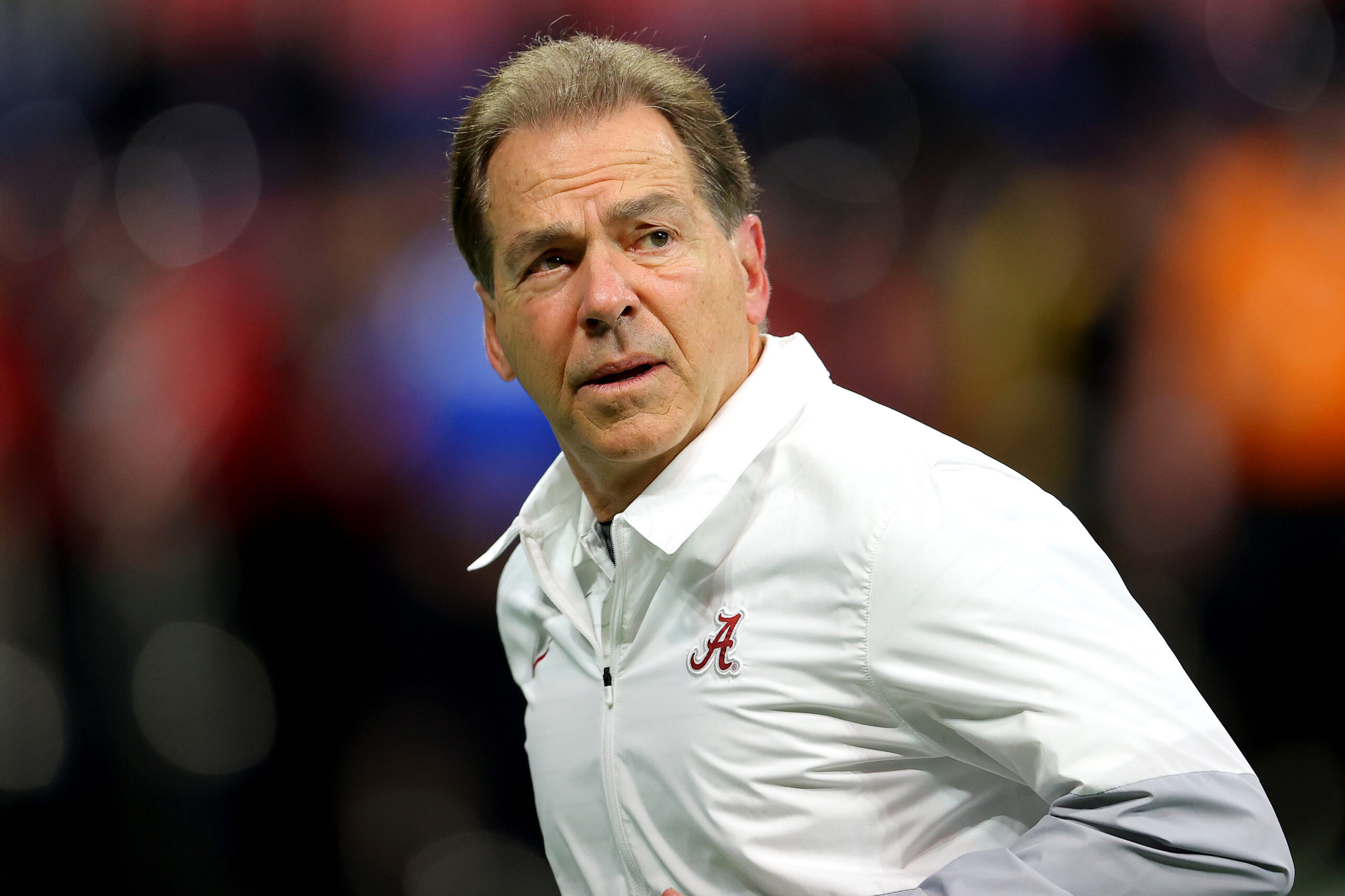

SEC member and college football power Alabama has 26,000 fans on its waiting list for football season tickets. Coach Nick Saban earns $6.5 million a year in one of the poorest per capita states in the country. In most U.S. states, the highest paid state employee is the university football coach.

In 2013, Bama opened a weight room with 37,000 square feet of racks, juice bars and nutrition stations. The university had replaced an impressive center with their new $9 million one, which features hydrotherapy pools, and even waterfalls.

By 2008, Texas had added the North End Zone with 2,100 club seats, 47 luxury suites, a food court, Starbuck’s and tutoring center. When Texas A&M ditched the Big 12 for the SEC in 2012, Aggie fans attributed it to University of Texas at Austin having its own TV network. Texas State Rep. Ryan Guillen of Rio Grande City introduced a bill mandating A&M and Texas still play each other. It did not pass.

Bob Ryan of the Boston Globe and ESPN’s The Sports Reporters told The Shadow League

I have no data, nor much in the way of specific anecdotal evidence as to how the realignment has affected travel, etc. But let’s talk common sense. Whereas Boston College once had Big East basketball games in Providence, Storrs/Hartford, Philadelphia and Jamaica, Long Island, they now have league games in Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and Florida. So what do you think?

Of how the shifts have impacted media, Ryan told us We aren’t covering Boston College basketball the way we once did, but Ws and Ls have a lot to do with that. Thus far, we are still covering BC football on the road. Speaking strictly as a fan, and not a writer, this re-alignment has taken something away from the experience nationwide. I struggle to place schools in the proper conference. Missouri in the SEC? Rutgers in the Big 10?

Even super-conference coaches have spoken frankly about the roots of realignment. Kansas State football coach Bill Snyder has said, “We have exploited college athletics in general and college football in particular…Its a message that the dollars and cents are more important than anything else.

Weve sold out to TV, and if I were in the TV field, Im sure wed want to promote all that we could for our business, Snyder acknowledged, but you think about games being played for money. Thats the intent of it, you play for money, so were playing games on you pick the night of the week. I think there are one or two nights we dont play college football. Its my feeling that we have exploited college athletics in general and college football in particular…Its been strictly about winning and dollars. Maybe dollars first and then winning second or vice versa, but you know, I think weve sold out to the dollars and cents. And weve sold out to TV.

Close to eight million youth played high school sports last year. The NCAA reports that only 170,000 athletes, about two percent of those who compete in high school, will earn a sports scholarship. Most of them receive far less than those in the large revenue generating sports: college football, and to a lesser extent, basketball.

The greatest expenditures support football, mens and womens basketball, womens gymnastics, womens tennis, and womens volleyball. In baseball, lacrosse, and soccer, scholarships are not nearly enough to cover the full cost of a college education. Though high school participation rates are the highest ever, NCAA limitations were put in place more than 40 years ago to ensure relative competitiveness, and check overspending, to limit these funds for most sports.

A Big 12 school, the University of Oklahoma, earned $135 million last year in ticket sales, sponsorships, and NCAA and conference distributions. The college spent $24 million of that money on coaching salaries, another $23 million on facilities and administrative costs. The 430 Sooner athletes on scholarship received about $12 million.

Consider major college swimming. Division I college swim teams may afford 14 scholarships for women and 9.9 for men. Yet most college teams have about 30 lady and 30 male swimmers. Swim coaches portion the scholarship money for the swimmers most likely to place in meets. The majority of the swimmers receive no scholarship money.

North Carolina State University competes in ACC sports, and is a charter member of the conference. Of N.C. States 558 athletes last year, 20 percent or less of had their expenses covered by scholarships. Outside of football, basketball, and the four other aforementioned revenue generating sports, only 27 Wolfpack athletes were on a full ride.

Last year, Atlantic 10 conference member (and former CAA school) George Mason University had 4.14 softball scholarship athletes, while the NCAA allows 12. The University of Cincinnati, which participates in the American Athletic Conference, supported 2.26 scholarships among its mens track team in 2013. Division I mens track programs allow 12.6 scholarships. The average NCAA mens track team consists of 40 athletes.

The Shadow League asked Howard Bryant of ESPN the magazine and The Sports Reporters his thoughts. Bryant said, “Well, I would say this is another cost of football. Everyone pays, either directly or indirectly, for a university prioritizing football over everything. The argument is that this prioritizing trickles down to the smaller programs and everyone benefits, but try telling that to the parents driving from Boston to North Carolina for an ACC volleyball game instead of to Providence or UConn.”

Do the super-conferences have rules governing athletic conduct, or sexual assault?

Jessica Luther, the author of Unsportsmanlike Conduct: College Football And The Politics of Rape, told The Shadow League, The closest thing we have to a conference-wide policy is the SEC and Big 12 policies that block the transfers of players into those conferences if they were dismissed from their previous team for violence against women. At this point, I am in favor of policies, including conference-wide ones, that hold the people at the top of programs accountable for cultural failure within those programs. The transfer policy makes sense to me but we should be asking why that applies to players and not, say, coaches or athletic directors. Seeing as the latter is involved in setting policy and the former are not, I doubt that would happen. But we should, at the least, be asking why that is.

Joining the SEC has been a football recruitment boon to Texas A&M, though there were other factors. The Aggies signed the fifth ranked class nationally for 2014. The current football team is partially the result of a recruiting class two years ago that was better than the classes of any of the other schools who joined the Big 12 since 2007. Though part of that appeal may be attributed to prospects having watched the 2012 season, when the Aggies went 11-2 and upset number one ranked Alabama featuring Heisman Trophy winning quarterback Johnny Manziel.

The old Southwestern Conference school TCU has also benefited from its move from the Mountain West to the Big 12. Horned Frogs football coach Gary Patterson said in a Nov. 19 story by Ralph Russo of the Associated Press that it would take “a few years” for TCU to have the roster depth of other SEC colleges..

Things have not gone as well in the SEC for former Big 12 (then the Big Eight) member, the University of Missouri. In football recruiting, the Tigers’ 2014 class was rated 13th in the SEC and 39th nationwide. Being an SEC East member, they must now recruit Florida and Georgia, where kids are more traditionally attracted to their own state schools and regional colleges.

Mizzou once recruited Texas quite well. That is no longer the case. The Tigers signed Dorial Green-Beckham, the leading prospect in the nation in 2012. Since then, the program has been beset by a threatened football team walkout after racial tensions on campus, and the resignation of Coach Gary Pinkel, who has non-Hodgkins-lymphoma.

Like Missouri in the SEC, West Virginia is a geographic misfit in the Big 12. Its current football squad stems from recruiting years nearly equal to those when Rich Rodriguez coached, though Mountaineer football averages of top state prospects choosing WVU is down from previous five year averages.

Colorado has not benefited from jumping from the Big 12 to the Pac-12 in terms of luring top recruits. The Buffaloes have had the worst, or near worst football recruiting years in the Pac-12 ever since, though that might soon change due to their run to the conference title game this year.

Of 15 highly sought after prospects in the state of Colorado in the last four classes, they have not signed one. Colorado officials felt moving into the Pac-12 would bolster recruiting in California, the state which produced its best players during the successful Bill McCartney years of the 1990s. California kids can weigh options at Cal, USC, UCLA, Stanford, and Oregon.

Utah has done fairly well in the Pac-12, though team success, not location, appears the reason.

Nebraska has recruited pretty well since it joined the Big Ten, despite firing Coach Bo Pellini in November 2014, and his replacement by former Oregon State coach Mike Riley, whose recruiting ties were all in the west (he was the longest tenured coach in the Pac-12).

What have been some of the worst conference moves?

College Basketball Hall of Fame member Dick Weiss of Blue Star Media said told The Shadow League, “West Virginia was a bad geographic fit for the Big 12. The closest road game (for them) is Iowa Sate. Fans can’t afford to travel to see the Mountaineers. They have to travel west to Texas for road games with Texas Tech. They win, but they spend so much to travel. More travel partners are already asking for scheduling relief.

BYU left the Mountain West to play football as an independent, and form their own TV network, but no one cares, Weiss added. Drexel and Delaware both left the American East where they were contenders, for the CAA. Both (basketball) coaches have since been fired. George Mason left the CAA for the Atlantic 10, and that coach has since been fired.

Pitt is a geographic outlier in the ACC. The conference brought in Pitt because of the schools well-earned reputation in Big East hoops. Then-basketball coach Jamie Dixon did well in Greater DC, Maryland and New York City, playing games close to them and their families, and road games in Madison Square Garden, and on national television in Syracuses Carrier Dome. That model was not sustainable in the ACC. Though Dixon was the Naismith Coach of the Year in 2009 and Sporting News Coach of the Year in 2011, he accepted the head position at TCU, his alma mater, in March 2016.

In realignment, schools dont leave what are perceived as superior academic conferences for lesser regarded ones. When Nebraska left the Big 12 for the Big Ten, it was viewed as an academic upgrade. The same may be said of Colorado leaving the Big 12 for the Pac 12, Utah leaving the Mountain West for the Pac 12, and both Missouri and Texas A&M leaving the Big 12 for the SEC.

Many would also feel the same concerning Pittsburgh and Syracuse leaving the Big East for the ACC, and West Virginia and TCU leaving the Big East for the Big 12, Rutgers moving from the Big East to the Big Ten, Maryland the ACC for the Big Ten, and Louisville the Big East for the ACC. But of course, The Big East was founded as a basketball super-conference in 1980.

What conferences have suffered the most from departures? The American Athletic Conference lost its largest university, Louisville, and also Rutgers, both major blows to its stature. And the current Big East, which again, was basketball oriented, no longer has regional rivals and traditional schools such as Boston College and Syracuse.

Winners other than the SEC, Pac-12, and Big 12?

Big Ten additions Maryland and Rutgers have brought millions of TV viewers from the Eastern Seaboard media markets. And the Big Ten was wise to follow the SECs lead, and realign its divisions geographically,

“Most expansion is football driven, said Weiss. The ACC took Syracuse and Pitt to level playing field with the old big East in basketball. It was Coach K’s idea. The Big East took Rutgers to get a piece of New York City. No one told them New York City didn’t care about college sports, and Rutgers will never make the postseason in football, basketball or women’s basketball.”

Power Five colleges may write their own rules regarding cost-of-attendance for athletes in each sport. The Power Five conferences (SEC, Big 12, ACC, Big Ten, Pac-12) make far more money than other leagues because of television revenue and the college football playoffs. The Big 12 schools each earned $30.4 million last year.

By contrast, the entire American Athletic Conference made $18 million. In fiscal 2015, the SEC reportedly made $527.4 million. The 14 Big Ten schools earned $36.7 million each, for a conference total of $513.8 million. Those two conferences have the broadest television reach of The Power Five schools.

Travel and scheduling are also issues of disparity. Where the super-conference football and basketball teams often fly charter, the wrestling, baseball, softball and volleyball teams do not. Some universities use buses and vans. After a game at Pitt in November 2014, Metro Athletic Conference member Niagaras womens basketball team was stranded on a bus in snowstorm for 26 hours.

Given the distances between some of the realigned schools, even non-eventful bus and van trips can seem endless. And by air, Penn State, for example flies its teams to games at Nebraska and Iowa, generally transferring to Detroit or Chicago, then Omaha.

When Maryland, Rutgers, or Penn State participates in large Big Ten tournaments in sports, it means trips to Chicago. Add the fact that Penn State is not near major airports in Pennsylvania to scheduling woes. And the athletic departments are tasked with finding new places for the teams to stop and eat.

Long trips also pose a disadvantage to visiting teams. Maryland, Penn State and Rutgers travel much longer to play Nebraska than do schools such as Illinois. To maximize these distances, when the easternmost Big Ten schools play Nebraska in a sport such as womens volleyball, they play Iowa the same week. This means missing more class time. Football teams avoid such worries by playing once a week and flying charter on most road trips.

How has conference expansion affected the source of much of the pro footballs Black talent of the 1960s through 1980s, Black universities? In many cases, visiting teams earn a million dollars to play major football powers. Historically Black colleges have afforded themselves of such opportunities. In 2013 only two players from HBCU’s were selected in the NFL Draft.

In 2015, Southern University played the University of Georgia, and lost 48-6. Consider the budget disparity. Southern spends about $9 million per year on its athletics programs. Georgia spends nearly $100 million. Thirteen of the 21 MEAC and SWAC conference schools had athletic budgets of less than $10 million in 2012-13, including Mississippi Valley State, at only $4.4 million per year.

The greatest receiver in NFL history, Jerry Rice, played for Mississippi Valley. He was the 16th player selected in the 1985 NFL Draft. Ed “Too Tall” Jones, a Tennessee State defensive end, was the first overall pick in the 1974 draft. The next year, Walter Payton of Jackson State was chosen fourth overall by the Chicago Bears. Nowadays those players would be at super-conference schools.

HBCU players also have the chance to play before some of their largest audiences. When Savannah State faced Oklahoma State in 2012, it was their first game attended by 60,000 fans. Their head coach, Earnest Wilson III, was a former assistant coach at Penn State.

The Tigers opened 2012 against Oklahoma State, ranked 19th nationally and sixth ranked Florida State. Savannah State lost the games by a combined score of 139-0. Their athletic department used the $850,000 it earned from each game to hire a full-time strength and conditioning coach, bring aboard two strength and conditioning assistants, purchase new video editing equipment to watch game film, and equipment and gear for Tiger players. The next season they played at No. 16 Miami losing, 77-7. Savannah State was paid $375,000.

The weekend after the Southern-Georgia game, Boston College routed Howard University 76-0.

The coaches of both teams agreed to shorten the last two quarters by five minutes each.

That fall, Morgan State University lost 63-7 to the Air Force Academy. Alcorn State University lost 69-6 to Georgia Tech. Grambling lost to Cal-Berkeley, 73-14.

Once, HBCU’s could compete with mid-major universities on the gridiron.

In 2015, Howard lost to Applachian State 49-0. Despite the mismatches, HBCU’s see the games as branding vehicles. In some areas, the schools are more equal. At halftime of the Grambling-Cal game, Grambling won the Battle of the Bands.

In the mid-to-late 1960’s, Grambling produced more NFL draft choices than USC or Notre Dame. Their games were syndicated on national TV, and their annual contest against Morgan State at Yankee Stadium, the Whitney Young Bowl, attracted a capacity crowd, and was announced by ABC’s Howard Cosell.

That era ended when SEC and Southwestern Conference schools began recruiting Black players from Louisiana and Texas.

After the economic downturn of 2008, Louisiana governor Bobby Jindal rejected federal stimulus money offered by President Obama, which 31 states had accepted ; Louisiana was the first to turn it down. For the 2007-2008 fiscal year, Grambling received only $31 million in aid. In 2013, that figure was just under $14 million.

Under the current college football playoff system in Division 1, future games pitting schools such as Georgia against HBCU’s could prove scarce, as strength of schedule is a major factor in how universities are both nationally ranked, and selected for the postseason.

“The ’90s are predicted to be moving in the direction of three super-conferences, each with a major network,” Arkansas athletic director Frank Broyles told Sports Illustrated in 1990 for that visionary article on conference realignment. No one has a better sense of such trends, and the motivation behind them (see Kansas States Bill Snyders admissions earlier in this piece), than the principal benefactors – The Power Five conference football coaches.

Bear that in mind every time you watch an SEC, Big Ten, or Big 12 football game, or the playoffs and bowls that bring them together.