I am Hispanic. Or is it Latina? Chicana, perhaps? How about if I just say American? I was born in California, raised in Arizona and currently reside in Washington. They’re all American states, right? I’m American.

On second thought, that won’t work. There’s no box on job applications or census forms for American. So, I’m left to call myself what the forms dictate Hispanic.

Not that I’m ashamed of that at all far from it. I’m proud of my Hispanic background. Most people who look at me naturally assume I’m some sort of Hispanic.

Some sort of Hispanic….

Ah, labels.

Labels allow for a neat and tidy categorization of a group. They help shape our identity in the eyes of others, whether we like it or not. Since I’m not White (Caucasian), Black (African-American) or Asian, I fall under the Hispanic category. Even then, it’s not as tidy as it may seem.

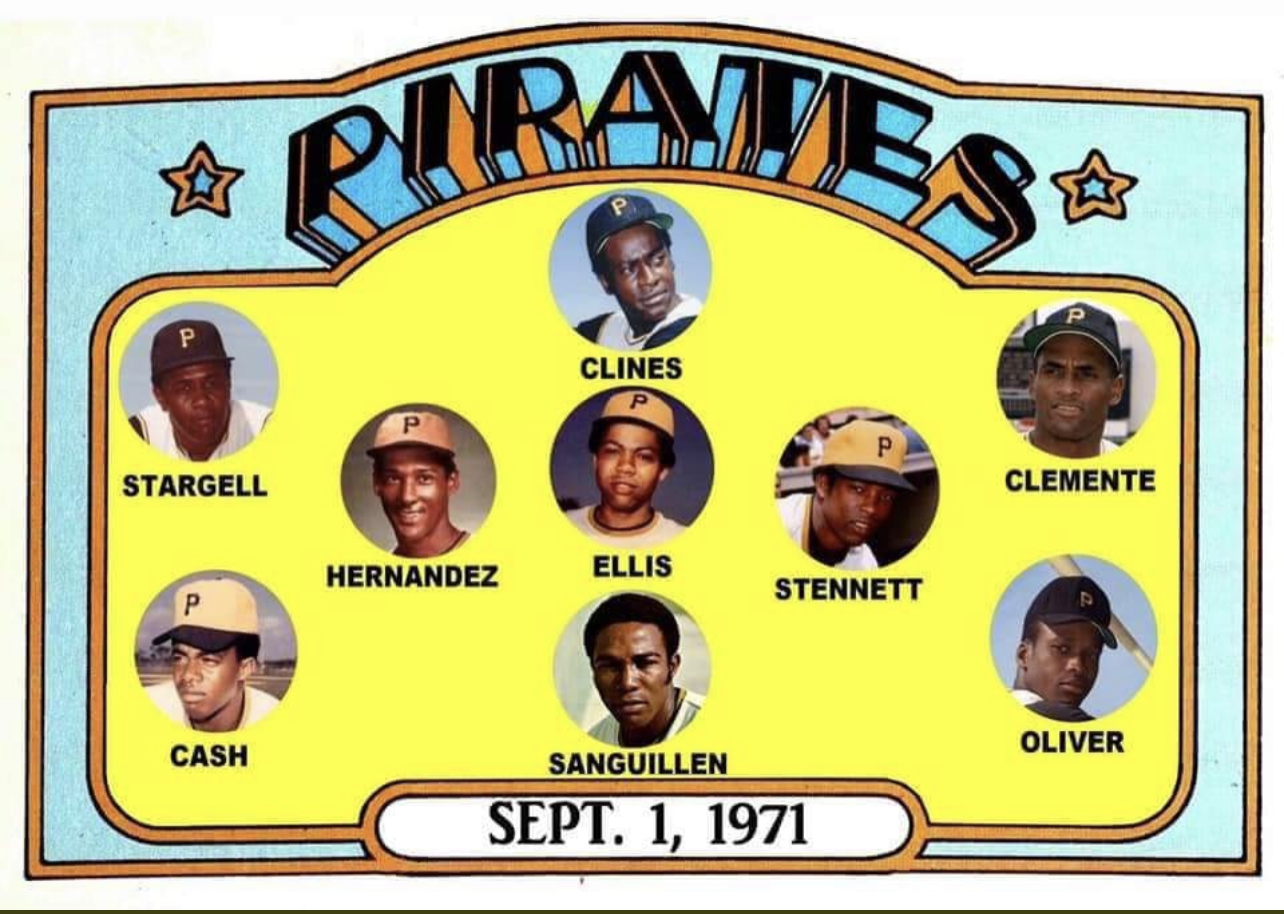

(Photo: Pew Research)

The Census picture above shows just how diverse we Hispanics are. Ask those in Little Havana in Miami, they’ll probably say they’re Cuban. Or those in Spanish Harlem (aka El Barrio); Puerto Rican is what you might hear, loudly and proudly.

Pride. There is an inherent pride in many of us. We are proud of our heritage, our culture, our families. The Spanish language unites us, but there are differences. Just as there are differences between someone from Chocktaw, Mississippi and Seattle, Washington, there are differences between Hispanics from Mexico and Hispanics from Cuba.

We are diverse in our cultures, food, music yet we are all labeled Hispanics or Latinos. As if we are all the same. That’s like saying a Cuban sandwich is the same as the Mexican torta. Or the Venezuelan hallaca is like the Mexican tamale.

Hint: they’re not the same.

Hanley Ramirez and Pablo Sanoval of the Boston Red Sox. Yovani Gallardo from the Texas Rangers and Yasiel Puig from the Los Angeles Dodgers. They are all considered Hispanics or Latinos yet they are very different. Ramirez is from the Dominican Republic, Sandoval is Venezuelan. Gallardo was born in Mexico and Puig was born and raised in Cuba. Gallardo grew up in Texas and The Lone Star state does not compare to the Castro-led Cuba that Puig grew up in.

But that’s the problem when we use labels.

We’re not all the same.

Even in sports, labels can define an athlete in the eyes of scouts and fans: smart, athletic, scrappy, finesse, slow, quick, tough, flamboyant, unselfish, game manager, high IQ, old-school. Chances are a few athlete’s names popped into your head. Say game manager and you might think of Trent Dilfer with the Baltimore Ravens and their Super Bowl run. Say flamboyant and the Dodgers’ Puig might come to mind. The racial undertones and underlying implications are obvious.

Puig, and others like him who are not from the United States, help make Major League Baseball one of the most diverse sports leagues in the world. Americans, Canadians, Mexicans, Australians, Venezuelans, Dominicans, Puerto Ricans, Japanese, Koreans and more all playing at the highest level in baseball.

When you see a Yasiel Puig, Yovani Gallardo, David Ortiz or a Robinson Can what do you think of? What about Felix Hernandez, Miguel Cabrera or Bartolo Coln? Does your mind struggle to remember what country they are from? Do you simply think Hispanic player or black player?

I know my baseball well enough to know where they are from and I automatically think Latino/Hispanic player. If you ask them about being Latino or Hispanic, chances are they will say they are Dominican or Venezuelan or Puerto Rican before saying Latino or Hispanic. Ever try calling someone from Jamaica “African-American?” The clarification will be delivered before the sentence is complete. It’s that inherent pride factor again.

Maybe that’s a similarity.

A consistent challenge for sports marketers is how to market to the Hispanic sports fan. As one of the fastest growing demographics in the United States, Hispanics are a prime marketing target for teams, leagues, brands and athletes.

There again, however, is the label. The grouping of all of us together as if we are the same. Marketers who don’t understand the complexities of our differences ask how to market to us in generalities. They need to speak our language.

What’s our language? It’s Spanish. It’s English. And yes, we even communicate in Spanglish. Even then, though, there are subtle differences in our verbiage. A Mexican sweet bread I grew up in Arizona calling pan de huevos, a friend from Mexico called them conchas.

Same bread. Same language. Different wording.

If a simple thing like bread can have different wording between two Hispanics, how can marketers expect to connect with Hispanics as a whole? They can’t unless they grasp how to speak our language.

Connection isn’t just a marketing buzzword. Connection is a common denominator among all Hispanic (Latino) nations. Connection with family, friends, social or sporting events and yes, even social media connection through communication.

That’s how we’re the same.”

That’s how to market and connect with (some sort of) Hispanics.

Speak our language.