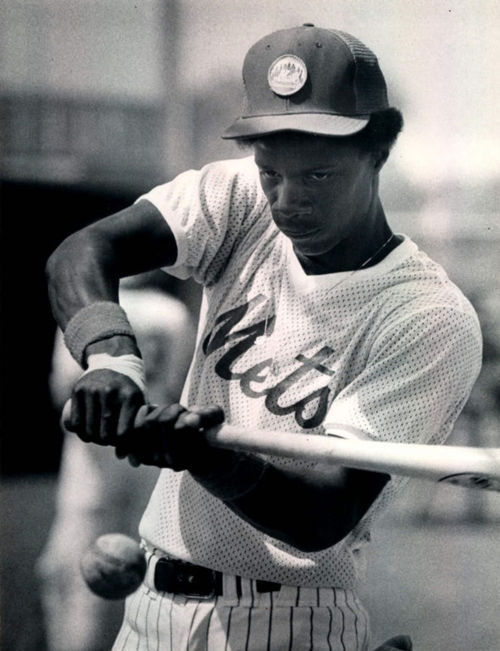

It was his swingit was always about his swing. There was a bravado in the batters box, a swag to the saunter at a time when swag wasnt in our lexicon. The same year I was born, on May 16th, Daryl Strawberry was brought up from the minors and started his first game with the New York Mets.

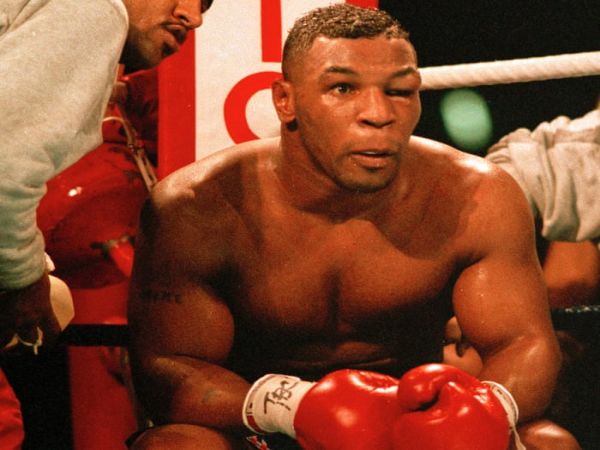

His saunter screamed a certain kind of emblematic Black Power, the one that would be released on a diamond made of grass rather than a street full of protestors, or cell of incarcerated what ifs.” It was the same feeling I got watching Tyson punch, the strength of a hundred broken homes and poverty lines fueling the gloves. I cried when he lost to Buster Douglas. I cried during the Tyson documentary because even with the brutality of past, there was a softness and strong tinge of regret in his speech, the kind that makes us forgive.

(Photo Credit: USA Today)

The Strawberry’s, the Rodman’s, Gooden’s, Jordan’s and Bo Jackson’s of the world would come alive with an unbridled, unabashed F— it, Im still here in eras of slum lords burning down tenements for insurance, displacing thousands upon thousands of black and Latin families in sections of the Bronx, pre-Reaganomics, post-Watts Riots, the failure that would be Boston busing and the crack epidemic.

I was born on January 10th, 1983. I was fortunate enough to have a big brother eight years my senior, one of those big brothers who inadvertently taught you about life and living by living his. He was my cultural hub, and the only thing resembling what could be a father figure and role model other than Heathcliff Huxtable (and we see how that panned out). So naturally, I turned to him for any and everything related to sports, music, and dealing with the opposite sex.

My brother was a die-hard Mets fan.

Littered about our Smurf-colored walls were Daily News, New York Post, News Dayclippings, and any other kind of paper you could cop for a quarter at the local newsstand near the bootleg man, near the Petland, on that corner of E. 188th and Creston Ave. in the Bronx in the early ’90s.

Those clippings, before the days of Instagram, Twitter feeds, Facebook algorithms and 24-hour news cycles, were our food source. Clippings of stolen bases, game-winning homers, shout-outs, almost there no-hitters, a sacrifice fly, broken records, line-up changes and trade deadlines.

(Photo Credit: tumblr.com)

There were also clippings of Hulk Hogan slamming Andre the Giant, and a young me assumed Pay-Per-View meant you would pay the paper people to let you view the World Wrestling Federation telecast we couldnt watch me being part of the last contingent of folks in my 4th grade class to get cable in our apartment.

There were clips of Patrick Ewing dunking on everybody before his knees told him slow down. And later, adorning the chipping paint job of the yet-born-again walls, were The Source Biggie interviews and Sports Illustrated covers with John Starks dunking on what seemed to be the whole city of Chicago.

There would be clippings of Mark Bavaro, hands in the air, saying all that he could say in Buffalo, and Leonard Marshall running with a pigskin cradled in his giant manpalms recovering a Joe Montana fumble, the fans knowing what that would mean to that team at that time during that game.

We got a collect call from our biggest brother from Elmira following Christies missed field goal. There would be Vibe covers with Diddy and B.I.G. before it became just Diddy, and Angie Martinez crying on the radio for what would feel like forever, 5-mic album ratings and free posters snagged from the HMV record store my brother worked at.

When we didnt have much other than our mother and ourselves, we had sports. And we had music…

You can read the rest of J Daniels’ story right here on blavity.com