Reporters are always asking me why I don’t sit-in or demonstrate for civil rights. I try to make my contributions for racial harmony in the best way I know how, on the baseball field — Willie Mays

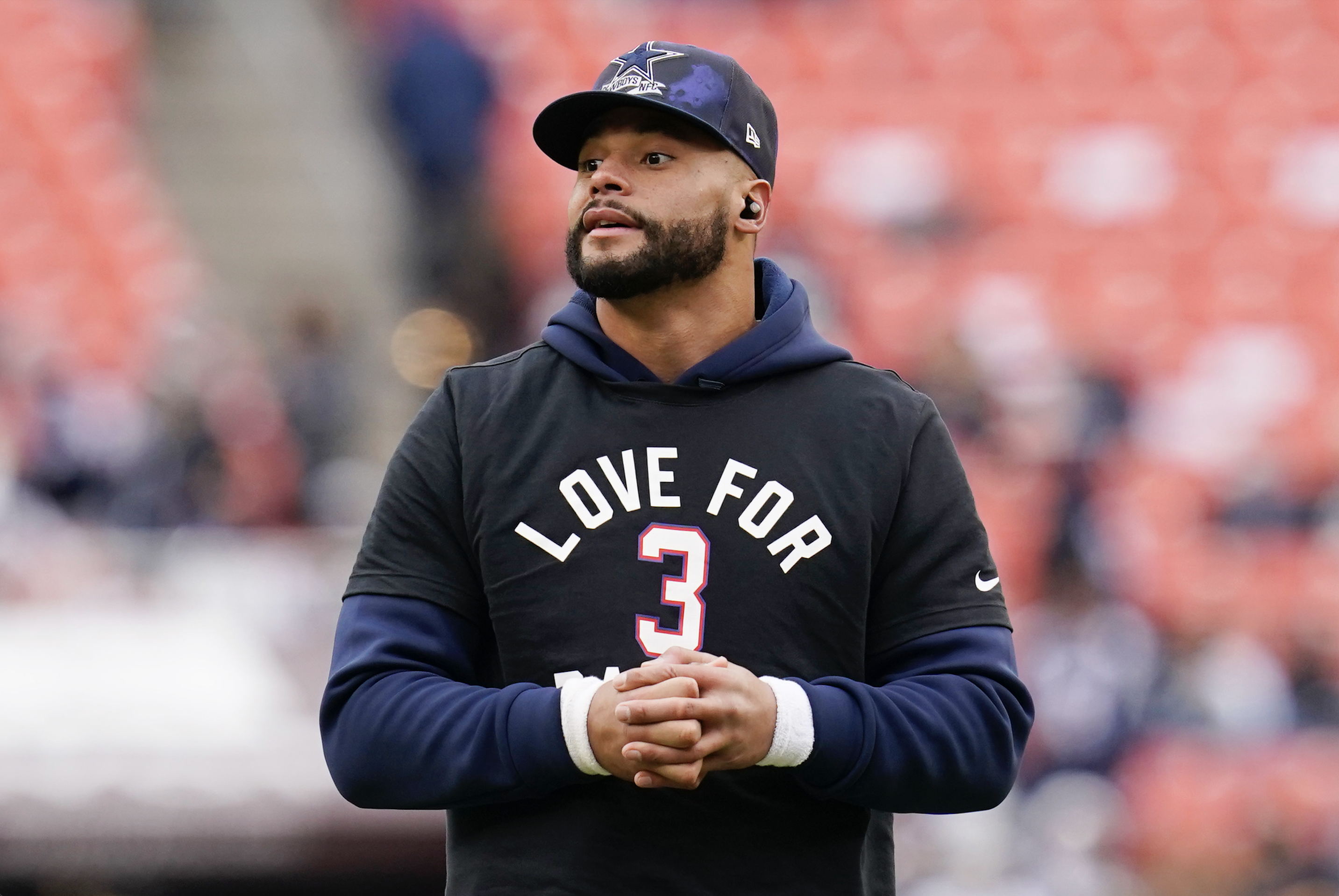

I never protest during the anthem, and I don’t think that’s the time or the venue to do so. The game of football has always brought me such peace, and I think it does the same for a lot of people… a lot of people playing the game, a lot of people watching the game, a lot of people who have any impact of the game so when you bring such controversy to the stadium, to the field, to the game it takes away. It takes away from that, it takes away from the joy and the love that football brings a lot of people. — Dak Prescott

***********************************

Last week, when a reporter asked about team owner Jerry Jones‘ policy that forces players to stand at attention during the national anthem if they want to be Cowboys, Dallas quarterback Dak Prescott had an opportunity to show real leadership and pushback against the draconian decision.

Dak disappointed.

Instead of standing in solidarity with other players who have protested or who are planning to do so, thus giving them the cover and support they need from a leader in the league, Prescott toed the line and played the role of the good quarterback. Dak declared that he would not protest during the anthem because protests took away from fans (read white fans) entertainment and joy.

He also argued that there were more effective ways to protest police brutality and social injustice. What?

When Prescott capitulated to Jones, however, he took the ire of many observers, (this one included) who believe that athletes have a right, and in many cases, a duty to use their public platforms to fight injustice. At the very least, they have to publicly stand in solidarity with others that do.

Prescott, like many black athletes, believes that his presence and play is enough. That is to say, he believes fans will see Dak as Dak and somehow that will translate into social justice. But that’s not the case. It never was. Not in Dallas. Not in any city. But instead of deriding Dak further, I want to offer a glimmer of hope. There’s room for the young quarterback to evolve.

Look no further than Abner Haynes, a superstar running back from Dallas who in four years went from refusing to protest to being a key cog in the most important protest in pro football history.

In 1961, Haynes, the star running back for the Dallas Texans of the AFL (they later became the Kansas City Chiefs) refused to get involved in a protest in Houston when black writer Lloyd Wells of the Houston Informer organized a local black boycott of Oilers games and asked all visiting black football players to join the movement.

At issue was the fact that black fans had to sit in segregated seating and black reporters were not allowed in the press box at Houstons Jeppesen Stadium. Wells argued that if black fans and writers could not sit in dignity and enjoy a game, then black players shouldn’t play.

What seemed like a tough ask of black players to risk their livelihoods by breaking their contractual obligations seemed reasonable to Wells. After all, in June he had organized a black boycott of the Houston Relays track meet and all the black athletes, including famed long jumper Ralph Boston, boycotted the meet.

Moreover, Wells understood that the upstart AFL heavily relied on black talent to compete with the NFL. And Haynes was the face of the league. Black players, especially Haynes, had the power to make a change.

Besides, this was the middle of the Civil Rights Movement, and black athletes had an obligation. They could no longer let white fans sit comfortably and only enjoy black athletes for their entertainment.

But despite the fact that Wells contacted every black player – the Oakland Raiders had police escorts in Houston to keep Wells from their players – no black AFL player joined the movement. After an October game when Haynes crossed the picket line, Wells went off.

Acknowledging the important role of the activist athlete, Wells argued, In these changing times and with Negroes new trend toward demanding social equality and acceptance on individual merits, instead of being treated as the part of a whole, that whole being a stereotyped group, we, as members of that group, should look with respect and admiration toward the Negro athlete who isn’t the grinning Tom that who by his skill and ability has reached the pinnacle of success in his sport, but lacks the character and personal integrity to stand up for all important principals of social and economical equality. And there are a few Negroes who are willing to risk personal fame and fortune in such cases, as Bill Russell, Woody Sauldberry and other members of the St. Louis Hawks and Boston Celtics did a few days ago in Lexington, KY, and that Abner Haynes and his teammates wouldnt do here two weeks ago.

In short, Wells called Haynes and every other black football players who played during the protest, Uncle Toms. Fortunately, Haynes evolved.

Four years later, a number of those same black athletes that refused to join an established movement in 1961 started a revolution of their own.

In January 1965, twenty-two black AFL all-stars refused to play in their game in New Orleans after experiencing racism throughout the city.

Abner Haynes & the 1965 AFL boycott

This video includes an edited clip from the 2009 miniseries, Full Color Football – Episode 2.

Remembering the incident more than 50 years later, Haynes recalled, We were disrespected as men. Haynes noted, We were not here because of color; we were here because of talent. Why should we go out there and put our lives on the line for people who don’t appreciate us? We were not appreciated here. Everyone agreed, you should not put your life on the line in that type of situation.

To be clear, every black player did not want to boycott the game. They feared for their careers. Some black players believed that there was a better way to protest. Others did not want to disappoint the fans that had already paid to watch them play. They all knew, however, that they had to stand in solidarity to be successful. They could not leave one of their brothers hanging.

But the move was not without controversy. Bold stances against racism seldom are.

A number of owners openly sympathized with the city of New Orleans, their mayor, and the games promoter. Even white teammates, who were supposed to have their back, got in the act.

Ron Mix, one of the white players who tried to get his black colleagues to change their minds, and wrote about the incident in Sports Illustrated, used a tired tactic telling them, I feel there are other methods that are better suited for this. We should stay and focus national attention on what is going on. News releases could pour out of here everyday.

In other words, Mix wanted his black colleagues to stay and play while facing the daily indignity of discrimination. He did not understand that by playing, nothing would change.

The Bills Ernie Warlick, the de-facto leader of the movement, cut him off and reasoned, Did it do any good when the Negroes on your team protested their treatment in Atlanta? No, it didnt. A definite action must be made.

In Atlanta, Warlick warned, black players protested prejudice, but decided to play. But not this time. Things would be different.

Still, Mix, did not listen. Mix refused to understand. At that point Haynes, the man who four years prior refused to join a boycott in Houston, said, We’ve got to do what we believe is right.

The face of his franchise, the running back who had carried the league for five years, had finally spoken. There would be no capitulating to racism.

The players show of solidarity had an immediate impact.

The AFL, which had used the all-star game as a showcase for a possible location in New Orleans, could no longer establish a franchise in the Crescent City. And in order for New Orleans to receive a franchise from the NFL, the mayor and governor promised the NFL sweeping civil right changes in the city and state.

Ironically, the 1965 all-star game moved to Houston, a city that had been integrated two years earlier, because local black activists bargained their support for a new MLB franchise for an integrated city. Houston got the Colt 45s and the black community got an integrated downtown.

For Prescott and other black athletes, and those who worry that Dak is in the sunken place, the move of Abner Haynes from a reluctant running back to revolting from the system is refreshing.

It is a lesson in solidarity and strength. It is a tale of black labor and black power. It is a reminder there’s always room for redemption. If players like Prescott can see beyond their own individual success and the needs of white fans, their platforms can promote change.