For better or for worse, there has been an increased effort to diversify the comic book realms of Marvel Comics and DC Comics over the past five years. Superheroes, many of whom have spent decades being household names, have been reinterpreted and transformed in ways that many have celebrated, while others have criticized. In essence, many of our favorite heroes have been changed from being ethnically Caucasian to becoming ethnically African American. On the surface this doesn’t appear to be a big deal. Historically, there has been a dearth of black superheroes in major comic book companies since their advent and it is only recently that Black characters have been written with any kind of depth at all at either of the major publishers. It has only been within the last 25 years that an African American owned comic book publishing company has even made inroads into the game with Milestone Comics, creator of such characters as Icon and Static Shock. Older comic book fans can recall the hackneyed manner in which both Black superheroes and villains were created back in the day and the condescending manner in which they were named.

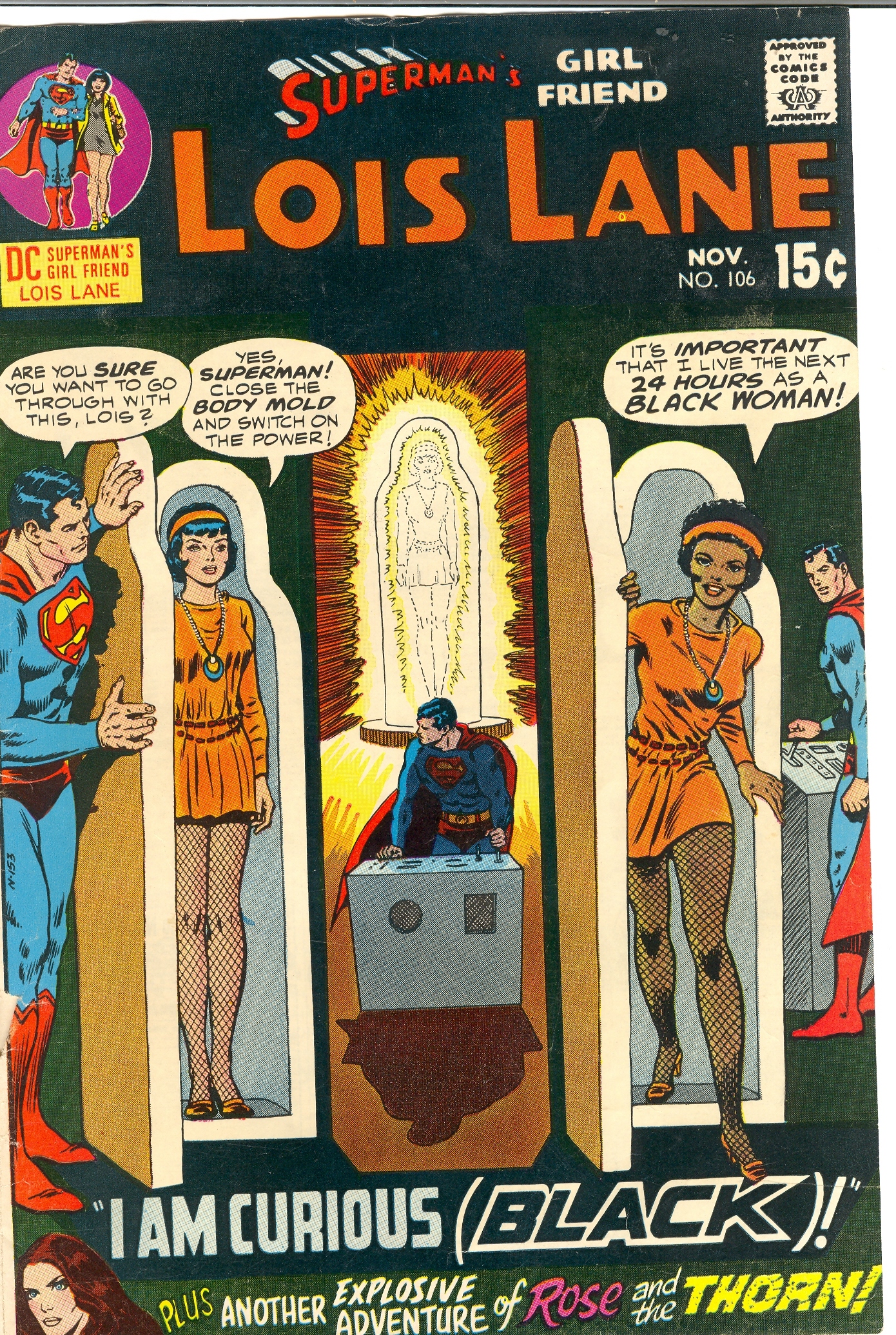

Black Vulcan, Black Lightning, Black Manta, Black this and Black that…and we know we weren’t alone in our surprise that Black Widow was a red-headed Russian spy upon her debut in Tales of Suspense #52 in 1964. Today we find ourselves in the midst of renewed efforts to change the overall complexion of comic book superheroes. But African American comic book fans are just like any other comic book fan in that we feel it is a mortal sin to alter or change a character without it being absolutely necessary to do so. In addition, we’re also aware that race is often used as a method to boost sales and attract interest to titles and characters that have become stale or to take advantage of a racially charged atmosphere in the general society to sell comic books. For example, in the 1970 DC Comic book "Lois Lane: Girl Friend of Superman", writers came up with the kooky idea that Lois Lane would gain access to a race machine and turn herself into a Black woman because she was “curious”. The Civil Rights era was still in effect as Martin Luther King, Jr was assassinated two years prior, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was still very active and the Voting Rights Bill had just been passed in 1964. Race and racial tensions were everywhere and while this appeared to be an attempt at using art as a conduit toward greater racial understanding, the lack of Black writers or artists involved in the creative process of the title in question showed that it was ultimately little more than lip service at best, sensationalism at worst. Though the 70s would prove to be a jumping off point for increased diversity in comic books, those first steps were clumsy.

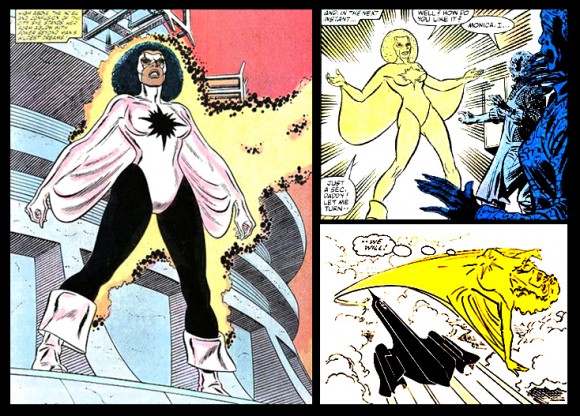

Today, over 40 years later, America finds itself at another racial crossroads as the promises made in generations past have only been partially kept. The illustrated idea of an increasing distrust of the federal government and the direction our country is going in was found in the pages of the critically acclaimed "Civil Wars" series from Marvel Comics. As has often been the case in the past, this is an example of art and life intersecting in the pages of comic books. We’ve been down this road before as the formerly white, cigar-chomping Nick Fury has been painted Black in the Marvel Universe and film as well. Also, the second Captain Marvel was a black woman named Monica Rambeau before Carol Danvers donned the name and uniform in 2012. Prior to that, Danvers was called Ms. Marvel.

With the recent recoloring of several very popular, and formerly white, characters at Marvel and DC, these publishers are bringing new energy to several of their signature characters. Captain America’s garb and guise have been passed on to his longtime friend and former sidekick, Falcon, because Steve Rogers is rapidly aging due to the removal of the vaunted super soldier serum. That new day of superhero-dom began in All-New Captain America #1. Is there any coincidence in this revelation being made a day after it was announced that the guise and power of Thor Odinson would be taken up by a woman? Probably not. Sensationalism or growth in art? One cannot be certain.

"As far as the recent trending of converting established properties to black or female I'm not a big fan," said urban sci-fi writer and blogger Thelonious Legend. "I understand the excitement but it's a microwave solution to appease the masses by leveraging the popularity of an established commodity. I would rather that they put some skin in the game and invested in creating diverse characters from inception. It's not a quick fix but you can cultivate and grow the stories/heroes as your audience grows with them. The audience will be more vested and it would be a great opportunity to showcase the skill and talent of diverse creators be it writers or artist who as of now have been invisible."

![]()

But there's really nothing new here. There have been brothers created in ol’ Captain Blue Drawer’s image before. There was Battlestar (first appeared in Captain America #323), who was also known as the fifth version of Captain America’s sidekick Bucky, who was named Lemar Hoskins. Although we have no doubt that his naming was ambiguous, calling a Black male character Bucky doesn’t sound copasetic in post Old Jim Crow America. The character was even convinced to change his name by another illustrated soul brother because of that connotation. Battlestar sounds a heck of a lot better. While Hoskins was never actually called Captain America, Isaiah Bradley was. His story was retconned into the Marvel Universe in 2003 in the Marvel title "Truth: Red, White & Blue #1". As the story goes, Bradley was experimented on to perfect the first super soldier serum before it would be given to a white man. Unlike the serum Steve Rogers eventually got, Bradley’s had multiple debilitating effects over time that were similar in nature to Alzheimer’s disease.

Sometimes the repainted versions of these heroes exist simultaneously with their white counterparts on worlds in other dimensions, while others exists in different timelines or are completely redesigned to erase their white counterpart in whatever timeline they exist in. Kid Flash, also known as Wally West, has been completely reimagined after the Flashpoint storyline in DC Comics and is now of African descent in "The New 52" universe. In addition, there is another universe in "The New 52" era that contains a version of the Justice League that is almost all Black. Their exploits take place in the pages of "Multiversity". Yeah, the name of their book sounds like something straight out of an Affirmative Action handbook from the Clinton administration; but the intent to put out more Black characters is understood and respected. Marvel’s Miles Morales had been celebrated as the Black/Latino Spider-Man for months before he actually appeared in the pages of "Ultimate Fallout #4" following the death of Peter Parker in the Ultimate version of the Marvel Universe. Initial outrage has since turned into respect and admiration for the character. There have been several Black Superman characters introduced in the DC Universe in the past but Val-Zod of Earth 2 appears to have staying power as he has already defeated the Clark Kent of his world after the later became corrupted by his own power. As you can see, it sometimes gets difficult to keep track of all the different versions of superheroes, especially when both DC and Marvel use alternate realities as a central theme in many of their titles.

Despite the consternation of many comic book purists, ethnic or female versions of our favorite characters will continue to be a device utilized by all comic book publishers. However, this measure ultimately appears to be little more than filler. Black characters written by mostly white writers sometimes come off as disingenuous, artificial and straight up racist. Not that anyone ever intends to write a character of African descent as a stereotypical boob, but when the new, Black Wally West is a troubled street kid with a love for vandalizing, and when a Black character once was proud to be called Bucky, we see that cultural awareness would have made all the difference. When one studies characters like Icon we can clearly see that he was originally created by someone who was intimate with the culture that spawned that hero, in this case it was creator Dwayne McDuffie and M.D. Bright in 1993.

But this is often lacking when a character simply reimagined as Black in midstream. No, it doesn’t matter whose writing these characters once they’ve got their legs underneath them. However, it would make a great deal of sense for them to be written and penned by individuals with an intimate understanding of not only the character’s powers, but the culture that makes them special, in the short term. Otherwise, these reimaginings come off as little more than a publicity stunt that should be ignored by comic book fans and not celebrated. Perhaps creating credible, powerful and original Black characters that stand on their on merits would be the best way to go in the near future.