“There is no such thing as black Italian.”

These were the chants Mario Balotelli heard while on the pitch for Inter Milan. Those chants exemplify the kind of attitudes which surrounded Balotelli growing up in northern Italy, the attitudes which appear to have shaped the character of the enigmatic, misunderstood striker.

Balotelli is no ordinary soccer player. From his teenage years, his attitude reflected that he knew he was the best. “I had him on the bench in a game when he was 13, something he never liked,” said Michele Cavalli, a trainer at A.C. Lumezzane, where Balotelli learned his craft. “I sent him on when we were 1-0 down, he took on the whole defense and scored, only to do the same thing again but this time screw the ball wide. We drew 1-1 and I was convinced he missed to punish me, but when I asked him he just smiled.”

It would prove to be a rare smile from Balotelli, who has asked why he should smile when he scores because, after all, that is his job (though he occasionally lets a hint of a smile out when scoring for Italy). He claims he will smile when he scores a goal in the Champions League final.

His problem may be getting on the pitch for such an occasion. His wild antics both on and off the pitch make him an extreme liability, constantly maddening his manager, Roberto Mancini, at his current club in England, Manchester City. During the first week of January, the two had to be separated after fighting during training. Balotelli frequently gets into trouble, drawing both yellow and red cards due to rash challenges when he fails to control his anger. His reputation doesn't help, as close calls tend to go against him.

Fighting is just the tip of the iceberg for Balotelli, though, whose off-the-field antics make Workaholics look tame. Before the biggest match of his City career, a clash against rivals Manchester United, fire engines were called when Balotelli burned part of his 3 million house after fireworks were shot out of his bathroom at 1 am . Naturally, he scored the opening goal (and the second) to begin a rout of City's hated United, then lifted up his jersey to reveal an undershirt that read, “Why Always Me?” His timing could not have been more apt; he appeared on a fireworks safety campaign the following week .

His other antics include: Visiting a women's prison with his brother because it “intrigued them”; giving a homeless man 1,000 after winning 25,000 gambling; finding a truant boy watching Man City's practice who was skipping school because of bullies, taking him back to school and confronting the bully for him; throwing darts from a first-floor window at the youth team as a prank ; and — in a strong submission for quote of the year in 2010 — he was involved in a car crash on his way to training and when police questioned why he had 5,000 cash in his back pocket, he simply replied, “Because I am rich.”

In that regard, Balotelli is in extremely rare company when it comes to minorities or immigrants in Italy, who, moreso than some countries in Europe, struggle to deal with racial tensions that swarm so many soccer games. Earlier this year, AC Milan midfielder Kevin Prince Boateng walked off the pitch after being subjected to repeated racist chants. The chants continued despite pleas from the PA announcer to stop, and the fact that it's 2013.

It is a problem that has long haunted the so-called beautiful game. It is a problem Mario Balotelli may, one day, help Italy and Europe overcome.

**********

Racism has been an integral part of the game in Europe since before the first World War. Franklin Foer recounts a tale of an all-Jewish team from Vienna in his excellent book, How Soccer Explains The World. The team formed in 1909 and was insulted everywhere they went, with common names ranging from “dirty jew” to “Jewish pig” during matches. After some sustained success, they actually managed to convert some gentile fans and won the championship, thanks to a goal scored by their keeper, only playing outfield because he broke his arm during the game. The team was disbanded in 1938 during Hitler's reign. Anti-Semitism, Foer explains, is no longer as much of a problem, though hardly because people are suddenly less ignorant. “Thanks to the immigration of Africans and Asians, Jews have been replaced as the primary objects of European hate.”

Balotelli's parents were some of those African immigrants, who moved to Italy from Ghana. Balotelli has always lived in Italy, though could not become an Italian citizen until he was 18, the rule for any immigrant in Italy. It ensures all foreigners are fully aware they are foreigners throughout childhood.

Italy is hardly alone with these issues – expressed through political, racial and religious forms – in the football world. Real Madrid and Barcelona, the two biggest clubs in Spain, represent Spanish nationalism and Catalanism, respectively. Fans of Red Star Belgrade in Serbia were literally used as an army for “ethnic cleansing” of Muslims and Croatians in the early '90s.

In Scotland, the most famous rivalry between Rangers and Celtic exists largely because Rangers fans are Protestant and Celtic fans Catholic. In the 16 th Century, the Protestant reformation led to murders and ethnic cleansing of Catholics in Scotland. In response, Catholics founded their own institutions, including Celtic, out of fear that Protestant institutions would take over and Catholicism would be forgotten. Protestants, in response, adopted Rangers as their own and a rivalry was born. Deaths and beatings still regularly follow matches, and managers of both sides have been subjects of death threats and bomb scares alike in the recent past.

Yet fans of both sides will claim they are not really racist, despite singing songs like, “We are the Billy Boys/You'll know us by our noise/We're up to our knees in Fenian blood/Surrender or you'll die” or the more direct chant, “F*ck the Pope.” The same holds true for Tottenham fans that dub themselves the Yid Army, “Yid” being a disparaging term for Jew in Yiddish. Fans of rival Chelsea began taunting them with chants such as, “Hitler's gonna gas 'em again/We can't stop them/The Yids from Tottenham.” The fans' response was to own the nickname, and anti-Semitic chants are now a regular fixture between the two.

Donald Findlay, former vice-chairman of Rangers, defended his vociferous and public support of Rangers to Foer, claiming the clubs weren't actually racist. “It's about getting into the opposition's head; it's a game; it's in the context of football,” he said. “Do you want to be up to your knees in Fenian blood? Don't be ridiculous.”

Alan Garrison, former leader of the Chelsea Headhunters, one of the most infamous and violent hooligan gangs in England, shares similar sentiments (he also shared an account of his hooligan days, under the alias Merrill, in a manuscript that was never published for being too violent and too right-wing). He spoke on a national scale, saying black fans took part in it too. “'I'm brought up here. I'm English. I don't give a toss if my parents came from the West Indies.' He'll fight for anything English. And he's in Combat 18, which is right wing. It's not racist right-wing. It's nationalist right-wing.” You get the sense that the attitude seeps down to the club level as well. After all, Garrison led Chelsea fans in anti-Semitic chants against the Yids on many occasion despite being Jewish himself.

But they were dishing out the insults, not unwittingly receiving them on the pitch. Besides, whether accurate or not, promoting racist and violent views certainly doesn't do anything to diminish them outside of the context of football. People fight and get killed over these words, particularly when alcohol is involved, and in Europe, it very frequently is.

The clubs don't do anything to help either. In fact, some embrace it. As Foer explains, “The clubs stoke ethnic hatred, or make only periodic attempts to discourage it, because they know ethnic hatred makes good business sense…they draw supporters who crave ethnic identification—to join an existential fight on behalf of their tribe.”

FIFA has done a woeful job of curbing racism, with futile attempts such as Kick It Out anti-racism t-shirts and ads. FIFA President Sepp Blatter was quoted as saying racism could be cured by a handshake in 2011. And whether the attitudes are genuine, or not, is completely irrelevant: World soccer is intricately tied to spreading hateful messages that are pervasive throughout society, a connection that should not be allowed to continue given the game's deep-rooted meaning in parts of the world. As Foer put it, “…soccer isn't Bach or Buddhism. But it is often more deeply felt than religion, and just as much a part of a community's fabric, a repository of traditions.”

If the beautiful game would like to remain so, it cannot continue to allow racism to be a part of that fabric or those traditions.

***********

“Is my heart not red like the others?” Balotelli would ask his school teacher. When he was growing up, he was one of the first black players to play in Italy. He suffered through racial abuse well before turning professional.

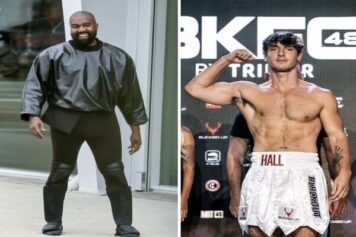

Balotelli was a trailblazer, Jackie Robinson-esque in that regard, as he was when he became the first black player to score for Italy. Now, there are black children on teams throughout the country.

It is a sign that racial attitudes are beginning to change in Italy, at least in the younger generations. But, for the generations before the Millennials, it's still dicey. Marcello Lippi, the former Italian national coach, told high school students that “cases of racism in football don't exist in Italy.” And while some Italians may be prepared to accept Balotelli as Italian, it comes with a catch. “Sure, Mario's totally Italian, ma è nero da paura – but he's so black, it's scary.”

These attitudes played out at Euro 2012, last summer. Balotelli, who recalled having bananas thrown at him in Rome, told reporters that he wouldn't tolerate racism in Ukraine/Poland – places so riddled with racist issues, several black English players wouldn't allow their families to travel there. “It's unacceptable,” Balotelli said. “If someone throws a banana at me in the street, I will go to jail, because I will kill them.”

He wasn't supported by UEFA. In response to his assertion that he would walk off the pitch if he heard racist chants or monkey noises – both of which were heard, but, apparently, ignored – UEFA President Michael Plattini announced players who walked off the pitch, even while enduring racial abuse, would receive a yellow card.

He was not pleased by his home nation, either. An Italian newspaper, Gazzetta dello Sport, ran a cartoon depicting Balotelli as King Kong . Several Italian fans showed up wearing blackface to support Balotelli, which, in the scheme of things, may actually have been a sad sign of progress.

But something else happened during Euro 2012 – the kind of thing that encourages young kids to stop supporting local Italian teams and start supporting Manchester City just because Balotelli “is so cool.”

During the semi-final game against Germany, Balotelli put Italy ahead 1-0 with a powerful header. When he later received the ball forty yards from the goal, tapped it down with his chest and began sprinting toward the German keeper, everyone watching sensed it would be a pivotal moment of some kind. Earlier in the tournament, though, Balotelli had blown a similar chance against Spain. What was going to happen next, especially in the context of Balotelli's life, was completely unknown.

As German captain Phillip Lahm uselessly gave chase, Balotelli unleashed a furious rising bullet into the top corner of keeper Manuel Neuer's net. He had no chance of stopping it. No one did. Balotelli turned, ran, stopped, and ripped off his shirt while flaring his nostrils and flexing. He didn't smile.

And there he was: A black Italian, in the flesh, letting everyone know who was singlehandedly responsible for taking Italy to the Euro 2012 Final.