Harris crossed the border from Pittsburgh to Morgantown and became a legend.

In the next installment of our continuing series, College Football Narratives, we visit Morgantown, West Virginia to speak with Mountaineers legend Major Harris, whose impact is still being felt by anyone who saw him play in the late 1980’s.

[jwplayer KUIPnVS5]

AWAKENED TO REALITY

On the night of June 27th, 1987, Major Harris was home in Pittsburghs Hill District. Hed come home for the weekend to visit some family and friends, and to enjoy some of the money in his pocket before intense two-a-day practices began for the upcoming football season.

Working for the West Virginia Department of Transportation that summer, the quarterback who would be playing his first college games as a redshirt freshman for the West Virginia University Mountaineers was excited about what laid ahead of him.

Strewn behind him was an extraordinary resume of athletic accomplishments at the prep level. In basketball, he was one of the best guards in the country at Brashear High School, a 6-foot-1, 205-pound marvel of strength, determination and instinct. As a junior, his squad was barely beaten by an exceptional team from Carlisle High School that featured two future college basketball stars North Carolinas Jeff Lebo and Syracuses Billy Owens. During his senior year, Harris posted 24 points, nine rebounds and three steals per game.

But as talented as he was on the hardwood, his aptitude on the gridiron dwarfed his considerable hoops acumen. With huge palms, which he often said made a football feel like a baseball in his hands, and a rifle for an arm, he could fling the rock through a monsoon without getting it wet.

While resting on one-knee at the 50-yard-line, he could easily sling the ball into the end zone. When he was 16 years old, he gunned a football more than 70 yards in the air on the last play of the game for a one-point, come from behind victory. They called him, The Brashear Bullet.

He was widely regarded as the best high school football player in Pittsburgh, and among the best prospects in the entire country during his undefeated junior and senior seasons.

His high school coach, Ron Wabby, could only sigh and shake his head at all of the football powers that wanted Harris to switch his position to defensive back as a contingency to their scholarship offers.

Major at defensive back? Wabby once told Sports Illustrated. Major couldn’t hit a teddy bear without apologizing.

West Virginia’s head coach Don Nehlen didnt need to be convinced and was adamant that he was interested in Major solely as his future signal caller.

After the spring game during his true freshman season in Morgantown, it became clear to former starters Mike Timko and Ben Reed, along with fellow classmate Browning Nagle, who would later transfer to Louisville, that West Virginia’s football future rested in Harris hands.

Back at home on that June 27th in 1987, Harris, his cousin and some high school buddies walked from his second-story apartment in a Hill District housing project to a fraternity party near the University of Pittsburgh campus. When they arrived, the revelry had already been broken up by local police who were instructing lingerers to disperse.

As he walked up, bottles began crashing into a parked police vehicle. Amid the sounds of shattering glass, Harris began walking away from the scene.

“I didn’t do anything wrong, so there was no need for me to run,” Harris said.

A few minutes later as he turned a corner, a police car came screaming towards him.

“Hold it there nigger!” Harris remembers the officer telling him. “Put your hands up, turn around and face the wall!

When he did as he was told, he was beaten mercilessly by the officer, who bashed his head in with his flashlight before choking him with it.

Harris covered his head with his arms and repeatedly heard an incensed voice seething, “I should kill you nigger,” as he began to lose consciousness. Had the event happened in this age of social media and ubiquitous cell phone cameras, the beating would have been front page news across the country. But back in 1987, it was barely mentioned outside of Pittsburgh and West Virginia.

“I’d never experienced racism before that,” said Harris. “People joke that I’m the original Rodney King,” he says through his normal hoarse baritone and an unnatural chuckle, smiling uncomfortably while touching the scars that still adorn his head.

He woke up in the back of that police cruiser, handcuffed, with his head, hands and clothes soaked in blood.

When he was uncuffed and instructed to sign his name at the hospital, the arresting officer immediately changed his tone. When he looked at the signature, the policeman said, “Major, why didn’t you tell me who you were. I saw you play in high school. You were so great.”

Harris spent the night in jail, but the charges were eventually dropped due to a lack of probable cause.

The incident did not diminish his kind, warm and personable nature. But from then, he’d forever be weary of racism’s toxic stains on America.

COLLEGE BALL

That fall, the Major Harris show debuted at West Virginia University. The Mountaineers got off to a 1-3 start after losses to Ohio State, Maryland and Pitt. But over the next three games, where they beat East Carolina, Cincinnati and Boston College by a combined score of 131-33, college football got its first glimpse of the player who would take WVU off the regional fringe and into the national spotlight.

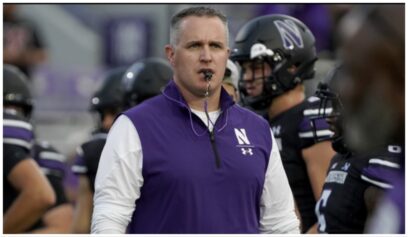

(Photo Credit: WVUsports.com)

They lost a 35-33 heartbreaker to Oklahoma State in a Sun Bowl game that was considered one of the most exciting of that postseason. On a frigid, snowy Christmas Day, the Mountaineers almost beat one of the country’s best teams. The Cowboys had finished the year at 11-2 after having only lost to No. 5 Nebraska and No. 1 Oklahoma.

Thurman Thomas paced Oklahoma State with 157 yards rushing on 33 attempts. Harris had a tough day throwing the ball, but he compensated by running for 103 yards.

“One of the things I remember about that game was how good Thurman Thomas was,” said Harris. “And as good as he was, I remember our coaches telling us that his backup, a kid named Barry Sanders, was even better! That’s hard to believe, isn’t it, that Barry Sanders was somebody’s backup once upon a time.”

West Virginia had most of its team returning that next season and with Major Harris flickering brilliance during his freshman year, Mountaineer fans were optimistic that they’d have a decent season. They had no idea that they were about to witness the greatest campaign in school history. They also had no clue that they were about to witness a signpost on the football highway, prompted by Harris play, that said Michael Vick, Cam Newton 500 Miles Ahead.

THE FUTURE OF THE QUARTERBACK POSITION HAS ARRIVED

West Virginia kicked off the 1988 season ranked No. 16 and won 11 consecutive games. It was the first time the school had ever gone undefeated and untied in 98 years of playing football. Harris threw for 1,915 yards and rushed for 610 more while accounting for 20 touchdowns.

But bringing his stats into the discussion is like saying The Godfather was a pretty good movie. You had to see it to appreciate the full breadth and depth of its genius. Same goes for Harris.

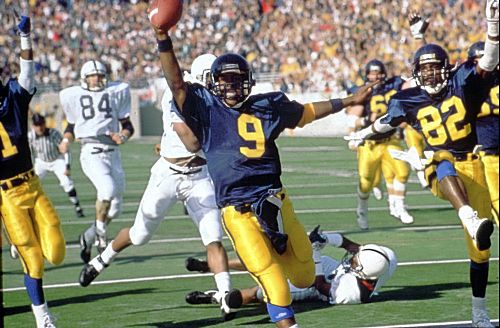

There are two plays that capture the wondrous majesty of his skills. The first one took place on their home field on October 29th against national powerhouse Penn State. In a scoreless game, Harris took the snap from center on a first-and-10 from the Nittany Lions 26 yard line.

He’d forgotten the play call at the snap and as the Mountaineers offense flowed left, Harris broke right, where at least five Penn State defenders were poised to decapitate him. Initially confronted by a defensive end, he proceeded to drop the defender with a hard two-step stutter move that was eerily reminiscent of Michael Jackson easing on down the road in The Wiz.

He then executes a hard left cut that drops a linebacker like Allen Averson dropped Jacque Vaughn, before slicing through the remainder of the Penn State defense with a mind-boggling series of similar sharp cuts to the left.

After eliciting pandemonium in the stands, he walked up to his coach and apologized for going off script.

Two weeks later against Rutgers at Giants Stadium in New Jersey, trailing 10-7 midway through the second quarter he threw a touchdown pass that literally traveled 50 yards on a rope, the ball never rising above 12 feet off the ground. The amazing thing was right before he released it, a defender was closing in from his blind side.

Sports Illustrated’s brilliant writer, the late Ralph Wiley wrote, “At the last possible instant, Harris sensed the pass rushers presence and reacted, looking like a man falling off a tightrope while hurling a dart.”

The Mountaineers skyrocketed up the rankings and were matched up against No. 1 ranked Notre Dame in the Fiesta Bowl. If they could secure the victory, they’d be crowned national champions. Harris had morphed into a national sensation, his legend floating far above the bracing mountain chills of West Virginia and Pittsburgh. In the process, he became instrumental in the ever-changing aesthetic of what a college quarterback was supposed to look like.

But on the third play of the Fiesta Bowl, with all of the country’s eyes glued to the television, Harris suffered a separated shoulder on the third play from scrimmage. West Virginia’s ultimate weapon played for the rest of the game, but he could not throw the ball. The Mountaineers lost 34-21.

Harris had the highest passing efficiency rating of any quarterback in the country that year. He averaged 8.4 yards every time he touched the ball, while passing for 1,915 yards and 14 touchdowns and running for an additional 610 yards and six scores.

“I played pretty good that year, but we had an excellent team,” Harris said when asked to look around the sparkling football facilities that the current team now enjoys. “All of my offensive linemen were seniors, we had an outstanding defense and some very talented running backs and receivers. People always say that I put WVU football on the national map. Thats not true. Our entire team did that.”

His essence can be summed up as all flash with plenty of substance. After a 31-9 victory over Syracuse during that magical 1988 season, he was talking with a recruit from Texas who was in town on an official recruiting visit. As he spoke with the highly-ranked high school player about coming to West Virginia, in between being mobbed by fans for autographs, he eyed the expensive jewelry that adorned the young mans neck.

With his normal convivial smile, he calmly told the recruit, through his trademark hoarse voice that rises barely above a whisper, I see you brought your gold with you. Next year, bring your moves, OK?

During his next and final season at West Virginia, he continued to confound defenses, despite not having as strong of a supporting cast that he enjoyed the year prior. The Mountaineers finished the year with a record of 8-3-1.

Harris finished third in the Heisman Trophy balloting after throwing for 2,058 yards and 17 touchdowns. He also ran for 936 yards and six TDs. He was the first quarterback in Division I history to pass for more than 5,000 yards and rush for more than 2,000 yards in a career. And the silly part of that is that he only played three years.

AN UNFORGETTABLE IMPACT

There have been many talented, electrifying players to pass through Morgantown since 1989. Cornerback Aaron Beasley, linebacker Grant Wiley, running back Steve Slaton, quarterbacks Pat White and Geno Smith, and all-purpose threat Tavon Austin are a few that immediately come to mind.

But none of them captured the country’s attention quite like Major Harris. His impact still resonates on campus today.

Try to walk with him through the immense mass of tailgaters that gathers before Mountaineer home games. Its impossible to move five steps forward without people walking up to hug him, snap photos and tell him how much they appreciate what he did for the university.

“Oh my god!!!” screams one strikingly beautiful, blonde-haired, blue-eyed woman as she poses to take a selfie with him. “My dad is not going to believe it when I send him this picture. You are his favorite player ever. HE LOVES YOU!!!”

There are many college football fans who followed the game in the late 80s who may not be West Virginia fans, but they feel exactly the same way.

In 2009, Major Harris was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame.